I.

Next year, when Steven Spielberg’s 1975 movie Jaws celebrates its 50th anniversary, it will no doubt be hailed as the film that invented the summer blockbuster, the first classic to be directed by a Baby Boomer, the first movie to be largely shot on the ocean, and the first in which the musical score was practically a major character. It significantly altered the way that Hollywood would henceforth promote films (heavy TV advertising), and it caused studios to seek out numerous similar projects—high-concept action films that often included non-human monsters. But before Jaws became forever associated with Spielberg, it was a hugely successful novel written by Peter Benchley. Nowadays, the film is still highly regarded while the novel, if not forgotten, is no longer much appreciated.

The novel was published on February 1st, 1974, although its 50th birthday party isn’t likely to be terribly extravagant. Benchley died in 2006 at the age of 65, and his cultural footprint is nowhere near as large as Spielberg’s. His biography is also quite different. Spielberg is a Jew who grew up primarily in Phoenix, Arizona. A mediocre student, he dropped out of Cal State Long Beach in the late 1960s and rapidly established a reputation as a cinematic wunderkind. In 1968, when he was only 21 years old, he signed a seven-year contract to work as a director for Universal Studios. Benchley was born in 1940, six years before Spielberg, and he came from a New England family that had been in America since its days as a British colony. His ancestors were largely members of the so-called “frozen chosen”—stiff-necked WASPs who were prominent in government, business, and society.

Benchley’s great-great-grandfather, Henry Wetherby Benchley (1822–67), served as lieutenant governor of Massachusetts and helped to establish the Republican Party. Peter’s grandfather was Robert Benchley, a co-founder (along with friends such as Dorothy Parker and George S. Kaufman) of the famous Algonquin Roundtable. Robert Benchley became one of the New Yorker’s first breakout stars, publishing roughly a column a week for the magazine throughout the 1930s. Peter’s father, Nathaniel Benchley, was also a successful writer and penned everything from naval thrillers to children’s books. His 1961 novel, The Off-Islanders, was adapted by Norman Jewison into the hit 1966 film The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming. It was the sixth highest-grossing film of the year and was nominated for a Best Picture Academy Award.

Like his father and grandfather before him, Peter Benchley matriculated at the exclusive prep school Phillips Exeter Academy and at Harvard University. He was blessed with good connections and these were certainly useful to a degree—they provided the young writer with name recognition and helped him to obtain an agent at International Famous Agency, which also represented his father. In his 2002 nonfiction book Shark Trouble, Benchley notes:

I was very fortunate to have an agent. As a favor to my father, one of his agents, a kindly and generous woman named Roberta Pryor, had taken me on when I was sixteen and had—mirabile dictu—actually sold a short story of mine when I was twenty. (I received one fan letter, from a woman who pronounced the story the single most execrable piece of rubbish she had ever read.)

That parenthetical is typical of Benchley. Bestseller lists of the 1970s were full of writers who tended to boast about their own brilliance—Erich Segal, Leon Uris, Harold Robbins, Richard Bach—but Benchley wasn’t one of them. Besides, the caricature of Peter Benchley as a nepo baby has never been entirely fair, as he lacked neither talent nor dedication. His widow Wendy (to whom Jaws would be dedicated) has provided an introduction to the Folio Society’s new 50th anniversary edition, in which she wrote:

When he was fifteen and sixteen, [Peter] undertook a challenge set by his father, to commit to writing four hours a day during the summer. He could either sit alone in his small room each day staring at the typewriter keyboard or produce a thousand words. His father knew that being a full-time writer was a tough life, so he wanted to test Peter’s desire and determination for the craft. He expected that a rambunctious, athletic teenager would tire of the solitude and soon opt for more stimulating pursuits. … Peter not only tolerated the discipline and isolation instilled in him by his father, he enjoyed them. At the age of seventeen, he began writing stories and sending them to magazines. He had all the qualities essential for a novelist: an intense curiosity, superb imagination, and the ability to always ask “what if.” … He read about nautical history, underwater archeology, marine biology, the succession of English and Spanish monarchs, great 18th- and 19th-century writers, and, of course, sharks and other marine life. Years later, when the opportunity arose to talk to a publisher about a potential novel, he was ready not only with a couple of plot ideas but with the tools to create the story and the characters necessary for a gripping yarn.

Benchley’s first book, a travel memoir titled Time and a Ticket, was published in 1964 and immediately vanished into obscurity. (It sold out its entire 5,000-copy first—and only—edition, but he claims this was because his grandmother bought most of them.) For a while he wrote obituaries for the Washington Post, and his first article about sharks appeared in Newsweek in 1965. In 1967, he became a speechwriter for President Lyndon Baines Johnson, a gig that ended abruptly when Johnson opted not to run for re-election in 1968.

By the early 1970s, Benchley and his wife and their two young children were living in a house in Pennington, New Jersey. For $50 a month, he rented a small office space above a furnace supply company, where he did most of his writing. The 1970s were a financially unfriendly decade, and even many Harvard graduates had to struggle to make a living. At this point, he was scraping by doing freelance writing for the National Geographic and other magazines. Fortunately, his agent believed in his talent. In Shark Trouble, he writes:

Roberta refused to give up on me and encouraged me to have lunch with editors from publishing houses, a ritual that provided countless writers with vitally necessary meals and encouragement and, now and then, even generated a viable book idea. I kept two arrows in my quiver expressly for those lunches. One was a nonfiction idea about pirates—as in, a history of. The other idea was for a fictional story about a great white shark that lays siege to a resort community. Folded in my wallet was a yellowed 1964 clipping from the New York Daily News that reported the capture of a 4,550-pound great white shark off Long Island. I would brandish it at the first hint of disbelief that such an animal could exist, let alone that it might attack boats and eat people.

The protagonist of that news story was Frank Mundus (1925–2008), a charter-boat captain who led what he called “monster fishing expeditions” out of Long Island for many years. Mundus is thought to have been the model for the cantankerous shark-hating sea captain Quint, one of the main characters in Jaws (played by Robert Shaw in the film).

Benchley’s break arrived when he was invited to lunch by Tom Congdon, who was then a senior editor at Doubleday, a major American publishing house. On June 14, 1971, the two men met at a restaurant called Clos Normand and (over a seafood meal, appropriately) Benchley pitched his two ideas. Congdon was lukewarm about the pirate idea but told him to go home and write up a one-page synopsis of the shark idea for consideration by Doubleday’s editorial board.

A lengthy and deeply researched 1974 New York Times story by Ted Morgan provides us with the most comprehensive account of how that speculative lunch produced one of the most popular novels of the decade:

On June 23, Benchley’s one‐page description arrived. “The purpose of the novel,” he wrote, “would be to explore the reactions of a community that was suddenly struck by a peculiar natural disaster—not an earthquake or a flood ... but a continuing, mysterious devastation that, as time goes on, loses its natural neutrality and begins to smack of evil. ... Suppose a Long Island resort community was suddenly visited by a great white shark? A young woman is killed. ... How does the community cope with this inexplicable menace?”

Morgan reports that the editorial board liked the idea and offered Benchley $1,000 to write up the first four chapters. If Doubleday liked them, he would be permitted to continue and eventually receive an additional $6,500 upon the novel’s completion. But if Doubleday didn’t like the first four chapters, the project would be abandoned and Benchley would be expected to return half the advance, keeping the rest for himself (minus the ten percent his agent would receive).

However, Roberta Pryor balked. She didn’t believe that her client should have to return any of his $1,000 advance if Doubleday passed on the book, and this dispute nearly sank the project before it was launched. Doubleday argued that allowing authors to keep the entire advance on books the company ultimately decided not to pursue would set a dangerous precedent. But Pryor was adamant. “For me it was the principle of the thing,” she told Morgan. “Are they in the risk business or not? You want the publisher’s vote of confidence, not the money on a yo-yo.”

Jaws would eventually become a multimillion-dollar entertainment-industry juggernaut, but for several weeks in 1971, the entire project hung in limbo over a mere $500. Fortunately, Doubleday finally relented. Benchley was told that he could keep the entire $1,000 if he turned in the first four chapters by April 15, 1972. On March 20, 1972, 25 days ahead of his deadline, Benchley turned in the first 174 pages of a manuscript with the working title A Stillness in the Water.

II.

The opening chapter read pretty much as it would eventually appear in the published novel. A pretty young woman takes a midnight swim in the waters off Long Island and is killed by a massive shark. Much of the chapter is told from the shark’s point of view and elaborated with scientific explanations of how sharks hunt and feed, which gave the killing a cold and clinical quality at odds with the horrific human tragedy it described. Doubleday loved it.

Alas, the next three chapters were not at all what they were expecting. Benchley’s father and grandfather were satirists and wrote primarily in a comic vein. Nathaniel Benchley’s The Off-Islanders dealt with a Cold War confrontation between a New England fishing village and the Soviet submarine crew that washes up on its shores, but it was more interested in providing humorous social commentary on the subsequent culture clash than in delivering thrills and chills. His son seems to have taken a somewhat similar approach in the first 174 pages of his shark novel. “A funny thriller about a shark eating people is, I soon realized, a perfect oxymoron,” Benchley wrote in Shark Trouble.

To his credit, Benchley never bridled at the many editorial suggestions and rewrite requests that came to him via Congdon or from the book’s co-editor Kate Medina. As he later explained to Morgan, “When they insisted, I gave in. They’ve been in business a long time, and I’d never written a novel.” At this point in his career, Benchley still thought of himself as a nonfiction writer. The shark book was written out of financial necessity. This isn’t to suggest that Jaws is a piece of hackwork. It isn’t. Benchley obviously took a great deal of care with the novel. His willingness to repeatedly alter the course of his book at the behest of his editors seems less like the behavior of a literary hack than a survival strategy for a 30-something family man struggling to pay his bills. It also suggests a degree of humility for which artists are not exactly famous.

By April 28, 1972, Benchley had sufficiently amended the opening chapters for Congdon to formally offer him a publishing contract. On top of the $1,000 option, he would get $2,500 when he signed his contract, another $2,000 upon delivery of a first draft, and $2,000 more when the final manuscript was accepted. That $7,500 may not sound like much now, but in inflation-adjusted dollars it would come to roughly $55,000 today. That kind of money wouldn’t turn the head of a contemporary bestselling author like Stephen King or John Grisham, but almost any first-time novelist would probably be thrilled. And as soon as paperback publishers and movie studios began bidding on the rights for the novel, Benchley would find himself awash with cash.

On January 2, 1973, Benchley finally turned in his completed manuscript. Congdon and Doubleday were delighted, which is hardly surprising, given their extensive editorial input. Nonetheless, it was Benchley’s novel. The story was his own original idea and his keen interest in sharks infused the novel with awe and terror. The only thing that Congdon didn’t like about Benchley’s book was the title. A Stillness in the Water, he told Morgan, “sounded like a Françoise Sagan novel about a young woman who goes to the Riviera to forget about an unhappy love affair.” According to Congdon, a total of 237 titles were suggested and shot down. Days before the book was scheduled to go to the printers, Congdon and Benchley met for lunch in New York to try to settle the issue. As he recalls in Shark Trouble: “Finally, when we had finished lunch and Tom had paid the check, I said, ‘Look, there’s no way we’re gonna agree on a title. There’s only one word we agree on, so let’s make that the title. Let’s call it Jaws.’”

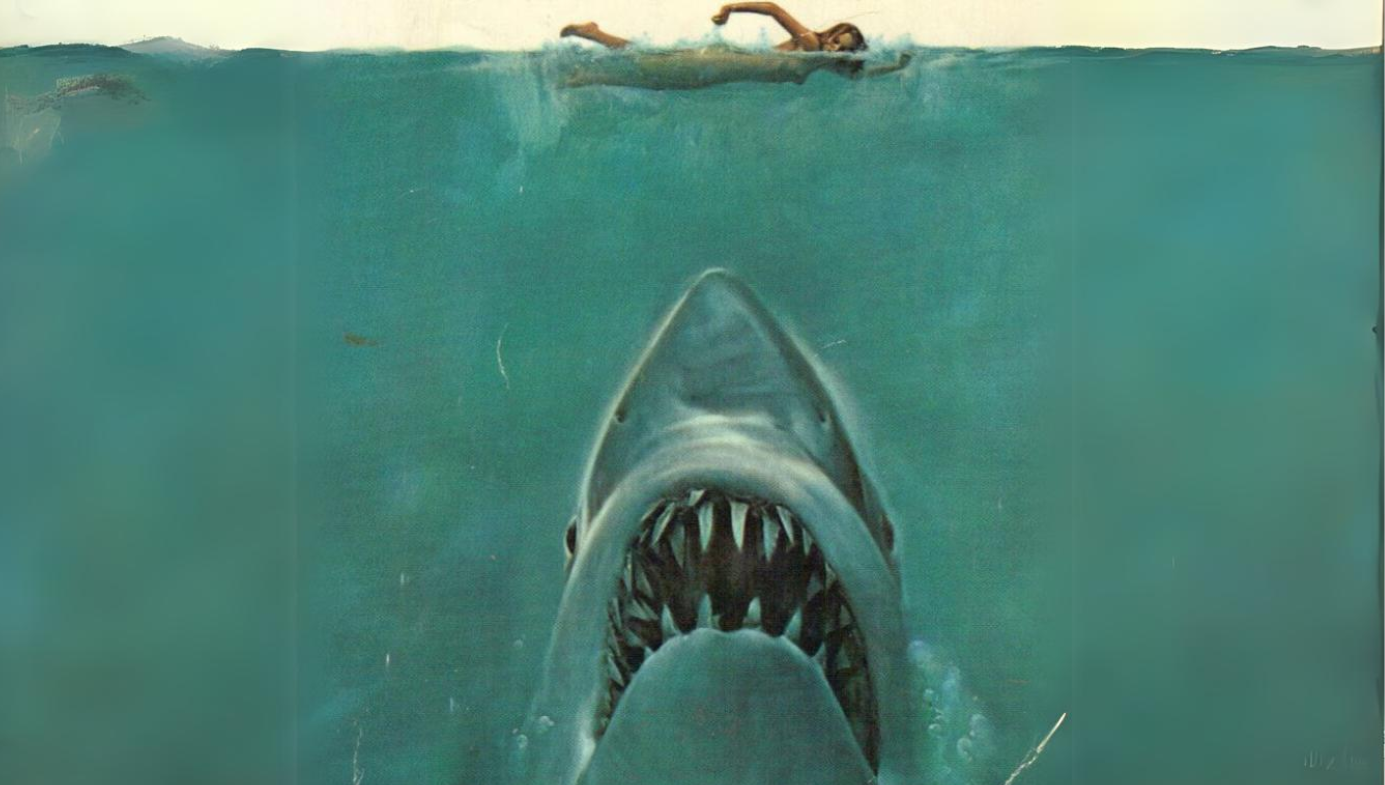

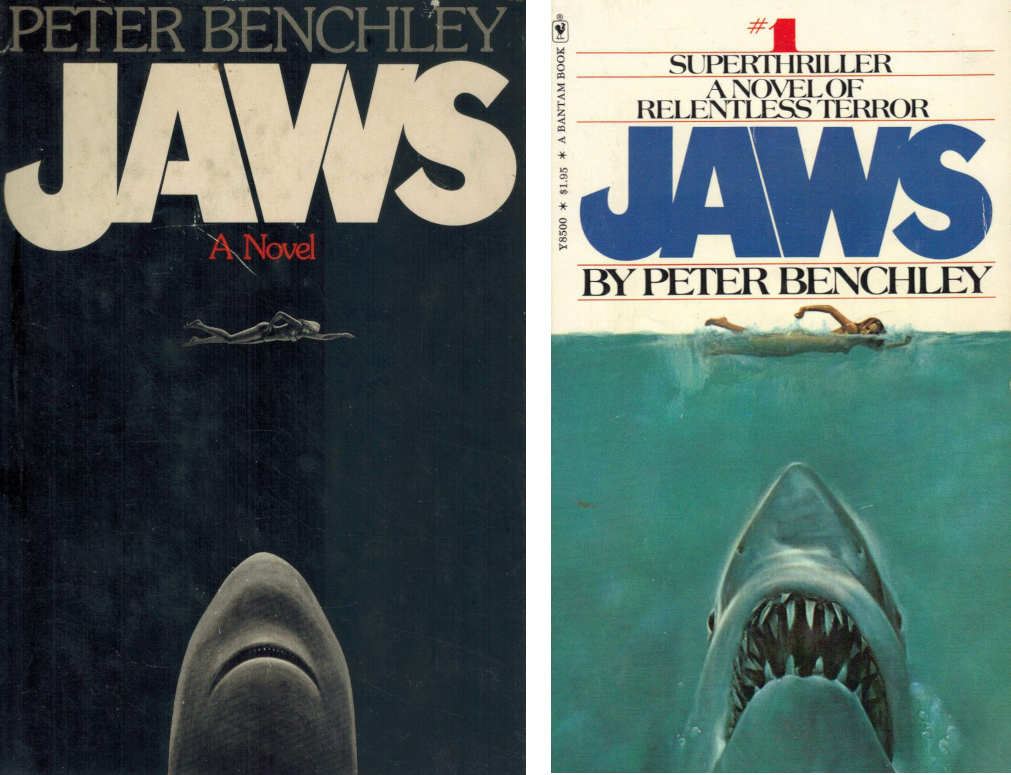

They still had a few problems to solve, however. Originally, Benchley had wanted the cover of the book to feature a bucolic Long Island beach town framed by a shark’s jagged teeth. A mockup of the cover was made but Doubleday’s sales force, the men who would fan out across the country and try to sell the book to American bookstores, objected that it reminded them of vagina dentata. Congdon asked his art director if the cover could simply contain a shark rising towards the surface of the sea. His art director vetoed the idea, telling Congdon that the cover wasn’t big enough and that the fish would look like a sardine.

At this point, Doubleday turned to legendary book-cover artist Paul Bacon, who retained the rising-fish motif but added a woman swimming on the surface of the water. This helped to illustrate the giant scale of the shark and also suggested the menace in the book’s plot. Congdon told Morgan that everyone at Doubleday realized that the new fish image “looked like a penis with teeth,” but the book now had a title, a cover, and was ready to be unleashed upon the American reading public.

III.

While all of this bickering over the artwork and the title was going on, Doubleday’s subsidiary rights department was busy negotiating with paperback publishing houses and subscription services. The book was sold to the Book of the Month Club, a subscription service that mailed out cheaply-made and discounted copies of newly published books to its tens of thousands of subscribers weeks before the publication date of the regular hardback. Those subscribers could opt to either buy the book or send it back unread. A BOMC presale usually boded well for a new book’s marketability. The book was also pre-sold to the Reader’s Digest Condensed Book Club and to the Playboy magazine Book Club, both of which were subscription services. These sales made the book profitable even before it hit the nation’s bookstores, and the money they brought in was split with the author.

In his Times profile, Morgan reports that Oscar Dystel, the president of Bantam Books, a paperback imprint, was reading a pre-publication copy of the novel on the commuter-train ride home from his office in New York City one evening and was mesmerized. He instructed Bantam editor Alan Barnard to offer Doubleday $200,000 for the paperback rights. That was a huge amount of money but the executives at Doubleday were torn. They worried that if they turned down the offer, they might never get another one as good. But they also thought it was possible that if they shopped the book around, they might be able to get as much as $300,000. Eventually, they opted to put the book up for auction, but they offered Bantam the right to top the winning bid if it chose to do so. Bantam ended up securing the paperback rights for the curious (but astounding!) figure of $575,009. Doubleday got half of that money. The other half went to the author.

Roberta Pryor sold the film rights to producers David Brown and Richard D. Zanuck for $150,000. She secured Benchley another $25,000 for writing the script (eventually he would share screenwriting credit with Carl Gottlieb, who was brought in “to do a dialog polish” on Benchley’s script; Benchley noted wryly to Morgan that describing Gottlieb’s rewrite as a dialog polish was like “referring to gang rape as heavy necking”). According to The Jaws Log, a nonfiction account of the Jaws phenomenon written by Gottlieb (whose relationship with Benchley was cordial despite the gang-rape joke), Peter Benchley had just $600 in his bank account on the day the paperback sale to Bantam was finalized.

On January 18, 1974, an article in Publishers Weekly noted that, “Peter Benchley has written a major novel, one that has created virtually unprecedented prepublication excitement. … Over $1 million in subsidiary rights sold; 35,000 initial printing, major ad-promo.” By mid-March, Doubleday had printed up 75,000 copies and was selling roughly 8,000 a week. By today’s standards, that may not seem like much, but the literary marketplace was very different back in 1974. For a start, the US had 120,000,000 fewer people. Furthermore, books were sold differently then. Nowadays, you can buy hardback books at your local grocery store, national supermarket chains like Wal-Mart, membership-only chains like Costco and Sam’s Club, in airport gift shops, and of course online. Back in 1974, almost all hardback book sales in America took place in bookstores, and most of those stores were small, local, independent shops. Large chain bookstores such as B. Dalton’s and Waldenbooks existed back then, but they didn’t have anywhere near the reach they would eventually attain in the final decade of the 20th century, just prior to the advent of Amazon.

So, in order to buy a copy of Jaws in 1974, the consumer had to make a special trip to his local bookseller’s shop. Hardbound books were marketed almost exclusively to those Americans who earned well above working-class wages. Jaws was priced at $6.95 in 1974, the equivalent of nearly $45 today. John Grisham’s latest hardback is currently selling for $19 at Amazon, marked down from the publisher’s list price of $29.95. And hardback books were almost never discounted by the retailer back then. The evidence suggests that a lot of those early copies were purchased by people who were not regular bookstore customers. Television had much to do with this. Benchley was a tall, handsome, erudite, and witty individual. Doubleday recognized this and booked him on as many talk shows and morning news programs as possible. But Jaws was also one of the few novels of the era that was advertised on TV directly to the consumer.

In The Jaws Log, Gottlieb recalls:

The book refused to fade. Quite the contrary. Week after week, it kept on selling, and pretty soon it became evident that Universal and Zanuck/Brown had a substantial hit on their hands. It is estimated that the hardcore hardcover book buyers in this country number around 60,000; these are the folks who want to read books when they are new; they make the bestsellers. When they’re through buying, it’s usually time to hit the airports and the drugstores with the paperback version. But Jaws showed signs of exceeding this basic upper limit, which indicated that most delightful of prospects—people were buying the novel who didn’t normally buy books. That meant a genuine grass-roots movement towards the property.

In Bestsellers: Popular Fiction of the 1970s, scholar John Sutherland dedicated an entire chapter to Jaws. It begins: “The term is often used loosely, but Jaws is a true superseller of the 1970s. In just six months as a Bantam paperback it sold over six million copies, and within a couple of years had come up to the maximal ten million mark. In Britain, Pan’s paperback sold a million in its first year and almost twice as many in its second, boosted by the film.” Jaws had been in print for less than two years when Alice Payne Hackett and James Henry Burke published their survey of American book sales, 80 Years of Bestsellers, but it had already managed to become the seventh bestselling novel of the 20th century, behind only The Godfather, The Exorcist, To Kill a Mockingbird, Peyton Place, Love Story, and Valley of the Dolls—all of which had been in print for years before Jaws was published.

IV.

Those only familiar with the movie might be surprised to discover that, as Sutherland put it, “Jaws film and Jaws novel are significantly different.” According to Spielberg, the final script contained 27 scenes that appear nowhere in Benchley’s book, most notably, Robert Shaw’s monologue about the sinking of the USS Indianapolis during WWII. Benchley’s book, on the other hand, contains several subplots that Spielberg opted not to use in his film. (These changes resulted in a brief spat between Spielberg and his normally congenial writer. After Spielberg was quoted making some unflattering remarks about Benchley’s novel in Newsweek, Benchley unwisely told a reporter from the LA Times, “Wait and see, Spielberg will one day be known as the greatest second-unit director in America.”)

In the film, Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) is presented as a reckless cynic, who pressures Police Chief Brody to keep the beaches open for financial reasons. He worries that the small businesses of Amity will suffer if the shark is allowed to keep tourists from swimming off the shores of the small community (in the film, Amity is a New England town; in the book it is situated in Long Island, New York). But in the book, Mayor Vaughan (for some reason, his name is missing the second “a” in the film) is a more sympathetic figure, who is coerced to keep the beaches open against his better judgement. Years earlier, when his wife was sick and he didn’t have the money to pay for her medical treatment, Vaughan accepted a financial “gift” from a prominent Long Island mobster. That mobster has since made significant investments in Amity’s real-estate market and worries that the value of his holdings will plummet if Vaughan allows the beaches to close.

The mob is also putting pressure on Chief Brody. At one point, a couple of goons drive up to Brody’s house and murder the family cat in front of one of his children. This mafia subplot adds to Brody’s woes. When he finds the dead cat in the garbage can, Benchley goes into full horror mode: “Lying in a twisted heap atop a bag of garbage was Sean’s cat—a big, husky Tom named Frisky. The cat’s head had been twisted completely around, and the yellow eyes overlooked its back.”

The book also includes a sexual affair between Ellen Brody and marine biologist Matt Hooper that never made it into Spielberg’s film. In fact, Ellen’s dissatisfaction with her life is a prominent subplot of the novel. She was raised in the East Coast’s upper class and educated at Miss Porter’s School (an elite institution, the alumnae of which include Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and Gloria Vanderbilt) and at Wellesley (though she dropped out after her junior year to marry Brody who, five years older than she, was already a member of the Amity Police Department). As a child, she merely summered at Amity.

Brody, on the other hand, was born and raised among Amity’s working-class full-time residents. Now that she is married to a townie, Ellen’s old friends tend to pity her and look down on her husband. This puts a lot of strain on the Brodys’ marriage, a subject that isn’t given any consideration in the film at all:

She hated her life, and she hated herself for hating it. She thought of a line from a song Billy [her son] played on the stereo: “I’d trade all my tomorrows for a single yesterday.” Would she make a deal like that? She wondered. But what good was there in wondering? Yesterdays were gone, spinning ever farther away down a shaft that had no bottom. None of the richness, none of the delight, could ever be retrieved. … She walked across the street and climbed into her car. As she pulled out into the traffic, she saw Larry Vaughan standing on the corner. God, she thought, he looks as sad as I feel.

Another aspect of Benchley’s novel that Spielberg mostly ignored concerned the economic struggles of the people of Amity. The 1970s were a decade marked by stagflation. After decades of growth, wages and union membership began to flatten as inflation began to rise. An oil embargo by OPEC caused a stratospheric surge in American gas prices. Martin Brody and the other residents of Amity are always worrying about money:

Like the rest of the country, Amity was feeling the effects of the recession. … Like all their friends on tight, fixed incomes, the Brodys shopped according to the supermarket specials. Monday’s special was chicken, Tuesday’s lamb, and so forth through the week. As each item was consumed, Ellen would note it on her list and replace it the next week. … Thursday’s special was hamburger, and Brody had seen enough chopped meat for one day.

When a local fisherman named Ben Gardner is killed by the shark (the appearance of his corpse provides the first big jump-scare in the film), Brody’s first concern is for Gardner’s widow, Sally. “I worry about her,” he tells Ellen. “Have you ever talked to her about money?” Ellen replies: “Never. But there can’t be very much. I don’t think her children have had new clothes in a year, and she’s always saying that she’d give anything to be able to afford meat more than once a week, instead of having to eat the fish Ben catches. Will she get social security?”

All this talk about the cost of meat isn’t accidental. For many American families, meat became a luxury in the 1970s. A recent article in the New York Times has this to say about meat prices then:

The price of beef was so high by then that boycotts and protests were organized against grocery stores. In the opening sequence of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Mary Richards famously rolled her eyes at the label of a meat package before tossing it into her cart. By 1973, Curtis Mayfield sang in ‘Future Shock’ about “the price of the meat / Higher than the dope in the street,” and President Richard M. Nixon had announced government price ceilings on beef.

Joshua Specht, a professor of history at Notre Dame and the author of Red Meat Republic, recalls how meat prices affected the American family man in the 1970s: “That is a time when there’s a breakdown of a certain kind of manhood and a certain kind of economic man. There’s a phase change in the economy, and that coincides with a change in the place of the male breadwinner. To be a successful man is to eat steak. And that breaks down in the ’70s.”

Benchley would likely have understood this link between meat and manhood on a personal level—he was a married family man at the time, struggling to make a living. Spielberg, on the other hand, was a young, childless bachelor embarking on his third feature film for Universal. The fact that he chose to shoot his film on Martha’s Vineyard—then as now one of the priciest housing markets in America—indicates that he wasn’t all that interested in the lives of America’s working stiffs. Benchley’s novel is set in a specific location (Long Island) and socio-economic milieu (the working class) and time (the 1970s). The film, like many of the movies that bear Spielberg’s imprimatur as director or producer (E.T., Close Encounters, Poltergeist, The Goonies, Gremlins, etc.), is set in a fantasy version of Middle America where people seem to be more or less immune from the effects of economic strife. Spielberg’s film could just as easily have been set in the 1950s, 1960s, or 1980s.

It may seem odd now that Spielberg’s film ditched so much of Benchley’s story. Contemporary films based on bestsellers generally strive to be as faithful to the books as possible, lest they provoke the wrath of the author’s hardcore fans. But that kind of slavish fidelity to a film’s literary source is a fairly recent phenomenon. For instance, Three Days of the Condor, which was the seventh highest grossing film of 1975 (Jaws was number one), was based on a James Grady novel called Six Days of the Condor. The filmmaker, Sydney Pollack, discarded much of the book’s material in order to make his film tighter.

V.

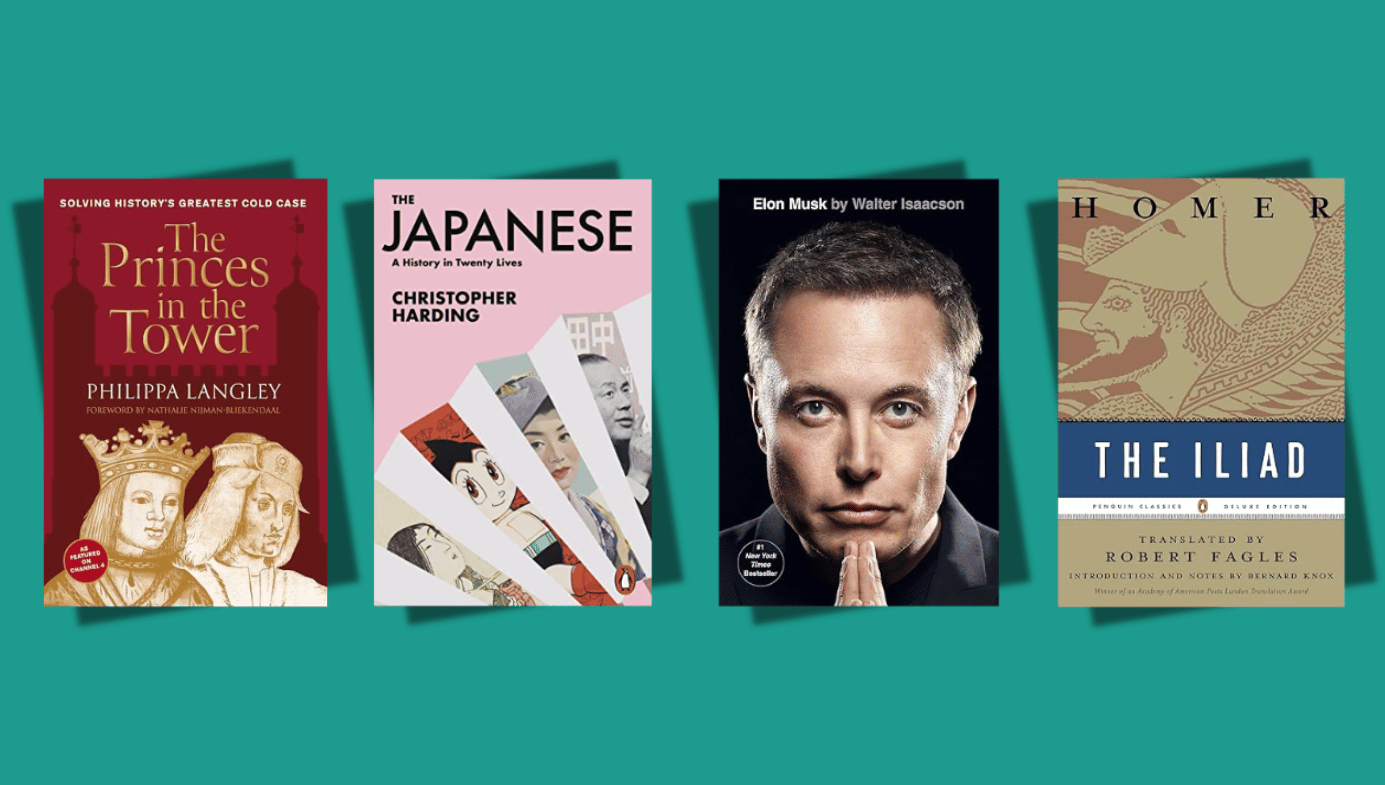

If they think of him at all any more, pop-fiction fans probably remember Peter Benchley as a one-book wonder. That isn’t entirely fair. It might be more accurate to think of him as a one-decade wonder. He cranked out two more bestsellers before the end of the 1970s. The Deep was the fourth-bestselling novel in America for the year 1976 and was adapted into a successful 1977 film by director Peter Yates. The Island was the 14th-bestselling novel of 1979 and was adapted by Michael Ritchie into a 1980 cinematic flop.

After that, Benchley was never much of a pop-cultural force at all. He published five more novels between 1982 and 1994, but none became a huge seller. Like John Denver, the Bee Gees, and Olivia Newton-John, he was never again as big as he had been in the 1970s. But as pop-fiction experts John Sutherland and Grady Hendrix have pointed out, Benchley’s Jaws inspired a lot of imitators. He may not have produced a lot of thrillers himself, but he blazed a trail for plenty of others. In his seminal 2017 work, Paperbacks From Hell: The Twisted History of ’70s and ’80s Horror Fiction, Hendrix amusingly illustrates how Jaws midwifed books about killer dogs, killer cats, killer rabbits, killer ants, killer slugs, killer maggots, killer scorpions, killer moths, killer worms, and just about every other kind of non-human creature on earth.

And not every offspring of Jaws was pure dreck. Hendrix cites Stephen King’s 1981 killer-canine tale, Cujo, as one of the more respectable entries in the genre. Sutherland identifies John Godey’s 1978 thriller The Snake as not only a true offspring of Jaws, but also one of the best:

One work which does, perhaps, deserve some attention is John Godey’s The Snake. In this novel the Jaws-like plot device (an eleven-foot Mamba loose and killing in Central Park) is made secondary to grisly comedy about New York’s free-floating, always-on-the-boil hysteria. In consequence, The Snake seems to be as much a satire on Jaws mania as an imitation of the other novel. … Godey’s novel focuses on the same trio of hunters as Jaws: an eco-OK herpetologist (who wants to save the reptile), a hard-nosed cop with a mid-life crisis and a vicious Jesus-freak sect who want to destroy the snake as the incarnation of evil.

The Snake includes passages that could have been lifted straight out of Jaws, in which the mayor of New York and the police chief argue about closing Central Park in the middle of a long hot summer. Godey (real name: Morton Freedgood) was a successful novelist whose 1973 thriller The Taking of Pelham One Two Three was made into a successful 1974 film (also co-starring Robert Shaw). He had been publishing novels since the 1940s, and he was a more prolific and more talented novelist than Benchley. Nevertheless, Jaws had become so influential by the late 1970s that even he felt compelled to crib from it.

Book critics in 1974 described Jaws variously as a thriller, a tale of suspense, an action story, and “the best man-vs-fish story since 1851” (Moby Dick was frequently evoked in reviews). John Sutherland noted that, “Essentially Jaws belongs not to the ‘literary’ tradition but to a bestselling entertainment fashion, or gimmick, of the early 1970s—the disaster story.” He was referring to novels such as Arthur Hailey’s Airport and Paul Gallico’s The Poseidon Adventure (as well as the hit films they spawned). But many, if not most, book critics of the era categorized Jaws as a horror novel. The reviewer for the Philadelphia Inquirer called the book a horror story and noted that, “Jaws proves once again that you don’t need demons or exorcists to create blanching, relentless terror.”

Today, horror novels and films tend to include some aspect of the supernatural. Without a supernatural element, they are usually just identified as gritty procedurals or supercharged thrillers. Back in the 1970s, however, pop cultural genres tended to be more loosely defined. Thus, Jaws, which possessed a monster but no supernatural component, was regarded by many as the best horror novel of 1974. Curiously, on April 5, 1974, two months after its publication, Doubleday published another unknown author’s debut horror novel, this one with a strong supernatural twist. Doubleday had high hopes for this novel and put out an initial print run of 30,000 hardback copies. Alas, only about half of those sold. The rest were remaindered or pulped.

But two years later, when Brian De Palma’s film version of the novel was released, Stephen King’s Carrie became a massive paperback bestseller. If you had asked a publishing-industry insider on New Year’s Eve 1974 to predict which of that year’s debut novelists would go on to become the most successful American horror novelist of all time, that insider would almost certainly have named Peter Benchley. Fifty years on, we now know that it was King who was destined to dominate American bestseller lists well into the 21st century. Benchley and his books, sadly, would be largely forgotten before the 20th century was up.

More from the author