Rescuing Identity Politics

Throughout his new book, Freddie deBoer resists the logical implications of his own argument. Can the "class-first" left actually put class first?

A review of How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement by Fredrik deBoer, 256 pages, Simon & Schuster (September 2023).

The left is undergoing an overdue reckoning. Progressive mass movements have achieved little more than mass in recent years. Occupy Wall Street didn’t beget economic redistribution, to say nothing of Marxist revolution. Large-scale marches for gun control and climate action produced neither. Following the police killing of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter blossomed into the largest social movement in U.S. history, drawing millions into the streets to demand racial justice, police reform, and even an “end” to policing. What they got instead were some statues taken down and municipalities quietly rolling back hollow promises to defund the police. Street protests and social media fervour dissipate as quickly as they roil over. Placards hit the garbage bins. Profile pictures boasting support for, as the meme goes, hashtag “the current thing” get changed out. The world moves on. Nothing fundamentally changes.

This perennial failure has led a number of left-wing commentators and spokespeople to issue diagnoses and critiques of their own political movements. A spate of recent books by authors from across the left-of-center political spectrum have converged on identity politics—and the concomitant demise of the universalist ethos among progressives—as the cause of so much dysfunction within social justice movements. The left-wing economic populism of yore has devolved into a toothless bourgeois progressivism more concerned with representation and cultural matters than material conditions.

Such arguments may be gaining traction, but they are not new. To their great credit, Marxist scholar Adolph Reed and literary theorist Walter Benn Michaels have been beating this drum since long before anyone cared to listen. No Politics but Class Politics, their recently released collection of previously published essays, argues that the contemporary left’s preoccupation with diversity and racial disparities distracts from and even undermines the class politics that once defined left-wing social movements by legitimating inequality—and, by extension, the economic order and political status quo—so long as that inequality breaks evenly over racial, sexual, and other identitarian categories. (Reed, in particular, is quoted on this last point so regularly that he can feel like an ageing legacy act forced out of retirement to perform his timeless hit forever.)

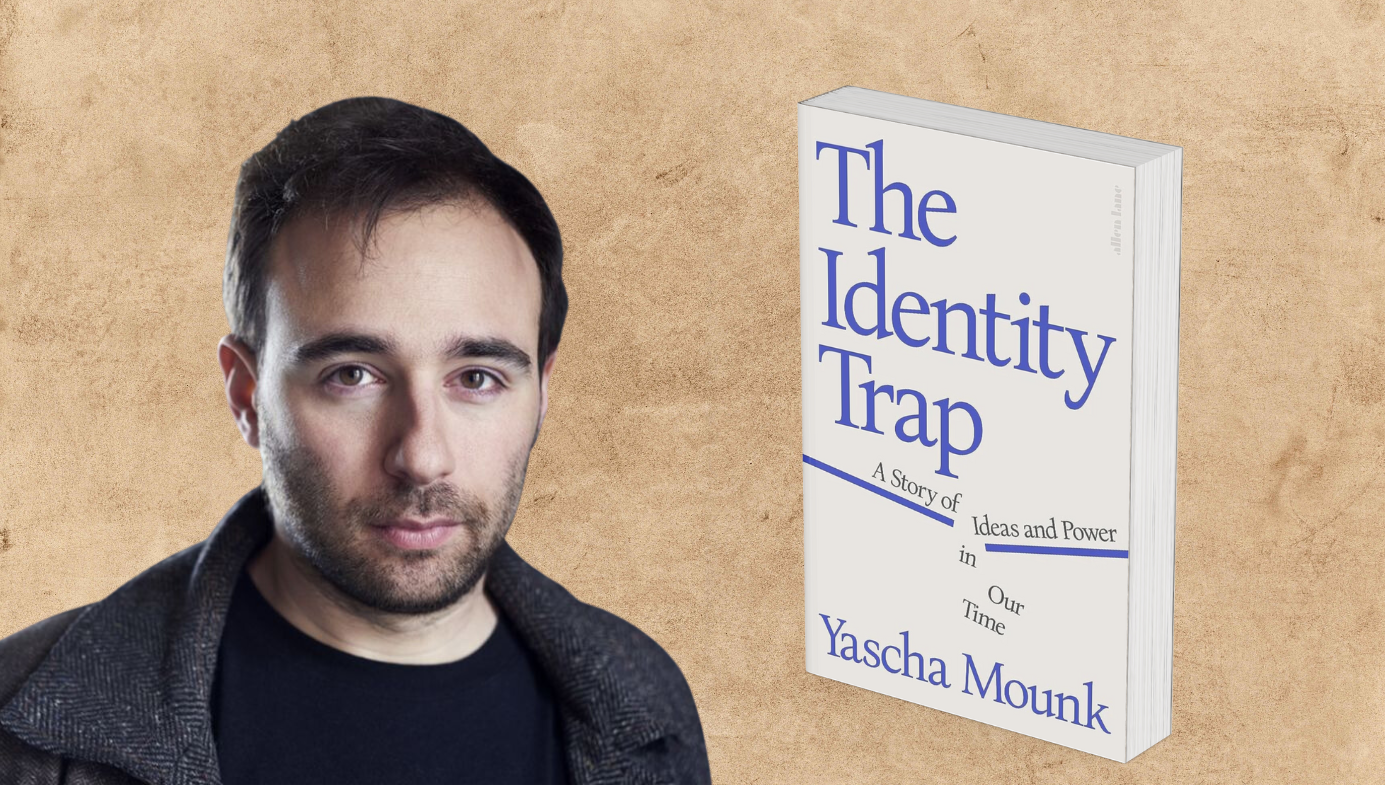

Reed and Michaels’s critique was initially focused on left-wing academics who had abandoned universalism in favour of postmodernist critical theory. They turned their attention to social justice movements more broadly only after once-esoteric academic theories, such as intersectionality, began seeping into public discourse in the age of new media and social media. However, many critiques of the left remain fixated on the “cultural turn” of the 1960s and 1970s, in which culturalist critical theory largely supplanted the Marxist materialist tradition in humanities departments. Take, for example, The Identity Trap: A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time, which also came out last year, in which political scientist Yascha Mounk traces the spread of progressive identity politics—which he dubs “the identity synthesis”—from humanities programmes and into other institutions and popular culture, which, he also warns, undermines social justice movements and weakens liberal democracy by breaking from the universalism that, once at least, undergirded both. Norman Finkelstein, a political scientist best known for longstanding criticisms of Israel and Zionism, gives a similar (if more rambling) account in his recent book I’ll Burn That Bridge When I Get to It!: Heretical Thoughts on Identity Politics, Cancel Culture, and Academic Freedom, in which he, too, laments how Foucauldian postmodernism, critical race theory, intersectionality, and similar academic theories reshaped left-wing politics. Social theorist Vivek Chibber takes a more conciliatory approach in The Class Matrix: Social Theory After the Cultural Turn, which attempts to revitalize the Marxist tradition by reconciling it with critical theory. Though no less critical of contemporary identity politics, Chibber takes culturalist critiques seriously as good-faith, if ultimately misguided, attempts to address real social problems. And so on and so forth—this is in no way an exhaustive list of recent diagnoses of the left.

Despite their merits, such accounts risk overstating the impact of academic theory on real world politics. The most compelling critiques of left-wing movements emphasize the class dynamics behind the cultural turn. Forget academia for a moment. Liberal and progressive political parties across the globe, including the Democratic Party in the United States, have been haemorrhaging working class support in recent decades, while relying ever more heavily on highly educated urban middle-class voters. This new coalition brings with it new priorities and preferences that have little to do with what gets taught in humanities programmes or published in obscure scholarly journals. Affluent progressives have material incentives to lean into a more cultural politics. The redistributive economic program called for by the Old Left and “New Deal liberals” is understandably unappealing to elite workers in the professional-managerial class. Affluent progressives naturally favour identity politics over economic populism, as the former poses no threat or challenge to the economic order or their own privileged place within it. Diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, as Reed points out, would merely recompose the individual strata of the economic order to be fairer internally, without doing anything to alleviate economic inequality across classes. Cultural progressivism is a progressivism that works for the most affluent members of society.

Author and activist Fredrik “Freddie” deBoer rose to prominence as a left-wing dissident spotlighting uncomfortable truths other contemporary progressives would rather sweep under the rug. Jocular and biting attacks on progressive pieties and hypocrisies earned him a sizeable media following, and his Substack was one of the platform’s early successes. My personal list of Freddie bangers includes, among many other incisive pieces, “Planet of Cops,” an essay on the hypocrisy of police abolitionists acting as cancel culture’s most dedicated enforcers, and “Please Just Fucking Tell Me What Term I Am Allowed to Use for the Sweeping Social and Political Changes You Demand,” which calls out social justice activists’ attempts to evade criticism through bad-faith rhetoric. (Interestingly, deBoer pulled both pieces from his blogs for various reasons, though the former has since been reposted.) Anyone only passingly familiar with his body of work might expect his own recent book-length foray into the genre of ‘where-the-left-went-wrong’ criticism, How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement, to join in on the critiques levied by the aforementioned critics.

To a large extent, he does. DeBoer faults affluent, identity-obsessed liberals for steering progressive movements away from material politics toward the frivolous and symbolic. Progressives are now more concerned with language policing and representation in media than addressing poverty or income inequality. This cultural turn is ascribed not to theorists in humanities departments but rather to a kind of “elite capture” of progressive institutions. DeBoer deconstructs the psyche and socioeconomic position of the American liberal, as well the perverse incentives under which liberals operate as the administrators of progressive institutions. The apparatus of the progressive movement—liberal media, Democratic campaigns and administrations, progressive think tanks, the countless non-profits doing progressive advocacy and providing community services, and, yes, much of academia too—is subject to the influence of not just the donor class but also of the professionals on staff. As such, progressive movements no longer serve the poor or the working class nor even the “marginalized” minority populations for whom they nominally advocate, at least not first and foremost. Progressive politics naturally reflect the values, preoccupations, and interests of those who lead and administer progressive institutions.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the emphasis on diversity. Those within or credibly aspiring to elite industries are understandably more concerned with the composition of elite professions than those from the working and lower classes, who have no material stake in how many black and brown faces show up on television or in boardrooms. But while minorities at large may not benefit from social justice identity politics, deBoer notes, professionals who happen to be minorities have certainly thrived in the era of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Economic data supports this assertion: 94 percent of new jobs at S&P 500 companies went to people of colour in the year following the George Floyd “Black Lives Matter” protests, according to data from Bloomberg, and women now outpace men as the majority of the college-educated workforce. When professional-class minorities advocate for diversity, they are advocating for themselves. Not to be left behind, many professional-class “good white men,” a concept deBoer has advanced before, can still further their own careers and social capital within the social justice paradigm by virtue signalling their good allyship and submitting to a faux deference politics in which, ironically, deBoer notes, they seem unable to stop talking about needing to sit their own white asses down and listen.

How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement offers an alternative path forward for social justice movements, not mere critique. DeBoer is far more concerned with praxis than theory. However, his case for a return to class-focused politics cites many of the same voices and intellectual traditions as the aforementioned critics. Where deBoer departs from much of the pack is in declining to reject identity politics. The book is not so much a critique of progressive identity politics as a defence. DeBoer bemoans “class reductionist” leftists who fail to appreciate the materiality of race, sex, gender, sexual orientation, and other identities. He writes: “Attending to injustices concerning these markers is not inherently a failure to be material; it’s only the expression of such politics that can fall into that trap.”

The concept of elite capture, as applied to social justice movements, is borrowed from philosopher Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò and his 2022 book Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else), yet another account of what went wrong with progressive movements. In an argument whose logic resembles the conservative mantra that “guns don’t kill people; people kill people,” Táíwò contends that identity politics is not to blame for the failures and dysfunction within progressive movements—the problem is the co-optation of identity politics by elites. (Real identity politics has never been tried!) For deBoer, who advances a similar logic, the problem with the social justice movement is not a programmatic error but merely ineffective strategy, bad messaging, and a misguided focus on the symbolic and immaterial. Progressives need not abandon identity politics. They need only focus on material outcomes rather than shallow symbolic victories. A more effective racial justice movement would stop fretting over Confederate statues and minority representation in media and devote more attention to ameliorating poverty in minority communities and reducing racial wealth and income disparities. (Despite citing Adolph Reed favourably on several occasions, deBoer often slips into the kind of “disparitarian” thinking Reed warns against.)

Class politics is presented not as an alternative to identity politics but as the best organizing principle for enacting a broader progressive agenda. Despite his mostly undeserved reputation as a contrarian, deBoer is a fairly conventional progressive. He identifies as such in the book and has corrected the record on his political positions, which align more or less perfectly with other mainstream progressives, on several occasions. Despite what his über-progressive detractors might assume (probably without actually reading his work), deBoer maintains that white supremacy and patriarchy remain hardcoded into American society and institutions, prefers much more open borders, and fully supports “trans-affirming” medical care and public policy. His dogged commitments to free speech and civil libertarianism more broadly are about the only positions that put him at odds with mainline progressives, some of whom have taken more illiberal or nakedly partisan stances on speech and censorship in recent years. He is, otherwise, a gold-star progressive. Though he acknowledges that many progressive social positions are out of step with the public, deBoer assures fellow activists and organizers that these, too, need not be abandoned. Progressives need only be more sensible about political strategy and how such issues are framed. Optics matter. Stop cathartically shouting your abortion and focus on electing pro-choice Democrats who will protect and expand abortion access. When possible, keep messaging focused on less divisive pocketbook issues.

Otherwise incisive books of political commentary often falter when pivoting from analysis to prescription and How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement is no exception. Much of the advice the final chapter offers progressive activists and organizers feels pedestrian in the manner of the self-help genre. Dream big, but temper expectations and focus on the achievable. Prioritize small wins that make a material difference over symbolic victories. Drop the academic and subcultural jargon endemic to activist spaces and progressive discourse. Explain how left-wing policies will improve people’s lives in plain language. Call out nonsense even when it comes from your own side. Above all, appeal to majorities and organize first and foremost along class lines.

This is all well and good, but without addressing the class contradictions and misaligned incentives derailing social justice movements, such advice amounts to asking progressives to Do Better. The book fails to take its own central argument seriously. DeBoer wants progressive activists and organizers to make common cause where, all too often, none exists. He writes: “Everybody has to pay rent. Almost everyone has lean months and hard years. Many people struggle to afford groceries; everybody, at some stage, feels wronged by the boss but unable to do anything about it.” But this is largely untrue for the middle- and upper-class progressives that make up the majority of the activist class. Many, certainly the most influential ones, do not struggle with rent or bills at all. They operate in a different economic reality than the poor and the working class.

DeBoer anticipates this criticism but has no answer to it. Open acknowledgment that few lefty tastemakers have ever wanted for anything is left hanging, and he resumes his call for affluent progressives to emphasize a shared economic struggle they do not, in fact, share. And so, when he urges them to “fight for everyone,” he is really asking them to fight for everyone else. Altruism is not common cause though, and deBoer confuses class solidarity with basic human empathy in an attempt to reconcile the conflicting material interests and cultural values of the professional-managerial class with those of the broader working class. The contradictions of the social justice movement are only acknowledged in the hope that they might somehow be resolved.

The book suffers for the attempt, as deBoer resists the implications and logical conclusions of his own argument. Each page is threaded through with equivocation, as critique gives way to apologetics. Every criticism comes bound up with its own equal-and-opposite ‘on the other hand…’ Progressives are out of touch with the public and the “marginalized” communities they claim to represent, but that’s OK because “political movements have always been driven by a vanguard” and activists are meant to be agents of change. Dividing people into identity groups is “inimical to solidarity,” but also progressive movements must cater to the particular needs of various minorities. Calls to defund the police and defences of rioting and political violence are counterproductive and misguided, but the protests of 2020 were nonetheless righteous and had “legitimate grievances and moral demands.” A whole chapter details the many ways in which the non-profit sector saps human and fiscal resources that might be better allocated to civil service programmes, unions, and grassroots organizations, only for deBoer to conclude that non-profits are nonetheless “essential to the basic operations of left-wing activism.” He bends over backward in service of the most charitable possible reading of the very elites who supposedly derailed the social justice movement. Affluent progressives and liberals may undermine movements for economic justice out of a self-serving obsession with frivolous symbolic politics but, deBoer somehow contends, they mean well. Though whole chapters are devoted to detailing the perverse social and economic interests that put affluent liberals in the professional-managerial class at odds with the poor and the working class, deBoer somehow decides that the former’s obsession with identity and symbolic politics is “only because of the strange and unfortunate cultural moment they find themselves in.” Pity the liberal, for he knows not what he does!

DeBoer won’t give up on progressives, no matter their faults. Republicans are dismissed as reactionaries and low-information voters. He regrets that the face of the progressive left is “some college-educated elite in a tony neighborhood in an expensive city,” rather than the common man, but insists that “you go to war with the coalition you have, not the coalition you wish you had.” His mission is thus, in his own words, to turn liberals into leftists. Of course, the trend has been in the reverse. Liberal identity politics have come to define the left, and class-focused movements, such as Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders presidential campaigns, are invariably co-opted by and subsumed into the broader identitarian progressive movement. In an omnibus review of recently released “anti-woke” books by authors spanning the political spectrum, including deBoer’s, Geoff Shullenberger notes that “It isn’t clear the class-first cohort has any response to these failures other than to keep trying.”

In the war for the soul of progressivism, the identity-obsessed liberals are clearly winning. There is no reason to expect this to change given the nature of the coalition. Progressive elites, as deBoer shows, are holding the reins. They won’t be persuaded into an economic populism that runs counter to their own material interests. A progressivism that works for the people, not the elite, is going to have to leave the latter behind.