Showdown in Champagne

In the tenth instalment of ‘The So-Called Dark Ages,’ Herbert Bushman describes the epic 451 C.E. battle that pitted Attila the Hun against Gaul’s Roman and Gothic defenders.

The article that follows forms part of The So-Called Dark Ages, a serialized Quillette history of Late Antiquity, adapted from Herbert Bushman’s ongoing Dark Ages podcast. This is the tenth instalment, and the fifth dedicated to the Huns. To read previous instalments, tracing the history of the Goths, click here.

[Attila the Hun] sent ambassadors to Italy to the [Roman] Emperor Valentinian to sow strife between the Goths and Romans, seeking to shatter by civil discord those he could not crush in battle. He declared that he was in no way violating his friendly relations with the Empire, but that he had a quarrel with Theodoric, King of the Visigoths. As he wished to be kindly received, he had filled the rest of his letter with the usual flattering salutations, seeking to win credence for his falsehood. In like manner, he dispatched a letter to Theodoric, King of the Visigoths, urging him to break his alliance with Rome and reminding him of the battles to which they had previously provoked him. Beneath his great ferocity, he was a subtle man, and fought with craft before he made war.

That’s how sixth-century writer Jordanes explained the beginning of Attila’s war in Gaul in 450 C.E. It was the first of two campaigns that Attila would launch against the Roman Empire’s western half. The first ended with the famous Battle of the Catalaunian Plains of 20 June 451, depicted by chroniclers of the time as nothing less than cataclysmic. In the second, which will be covered in our next instalment, Attila threatened Rome itself, but stopped short after his famous meeting with Pope Leo I.

By 450, for reasons that aren’t clear, Attila’s relationship with the Western Empire’s de facto leader, Flavius Aetius, seems to have broken down. While Priscus of Panium (whom we met in the last instalment) relates a scandal involving an arranged marriage with one of Attila’s retainers that may help explain the friction eroding the relationship, historians aren’t really sure why Attila chose to turn to war in western Europe. Publicly, he put out that his intention was to wage war on Theodoric’s Visigoths, who’d been settled in Aquitaine (southwestern France). But that just substitutes one question for another: Why would Attila wage war against the Visigoths? (Disambiguation: The Theodoric we’re talking about here is Theodoric I, whom we met in the fifth instalment of the Gothic arc—not the better known Theodoric the Great, who won’t be born till 454.)

We’ll start by taking a step back and looking at what the Visigoths have been getting up to since settling down near the Atlantic coast in the early fifth century, under the auspices of then-soon-to-be-Emperor Constantius III. From a territorial core centered around Toulouse and the banks of the Garonne River, they’d provided military muscle in the Romans’ ongoing struggles against the roaming brigands waging what became known as the Bagaudae Revolt.

Over time, the Visigoths widened their territories and influence, in part by providing direct protection to local Gallic elites who, being unable to rely on the beleaguered Roman state, now increasingly put their safety in the hands of Goth and Hun mercenaries. Rome now struggled to keep Gothic ambitions in check, as a semi-ritualized military march on Arles became a nearly annual undertaking as a means for the Goths to extort money and resources. Paying off this protection racket was expensive and annoying for the Romans. But they (not unreasonably) concluded that the alternative was worse.

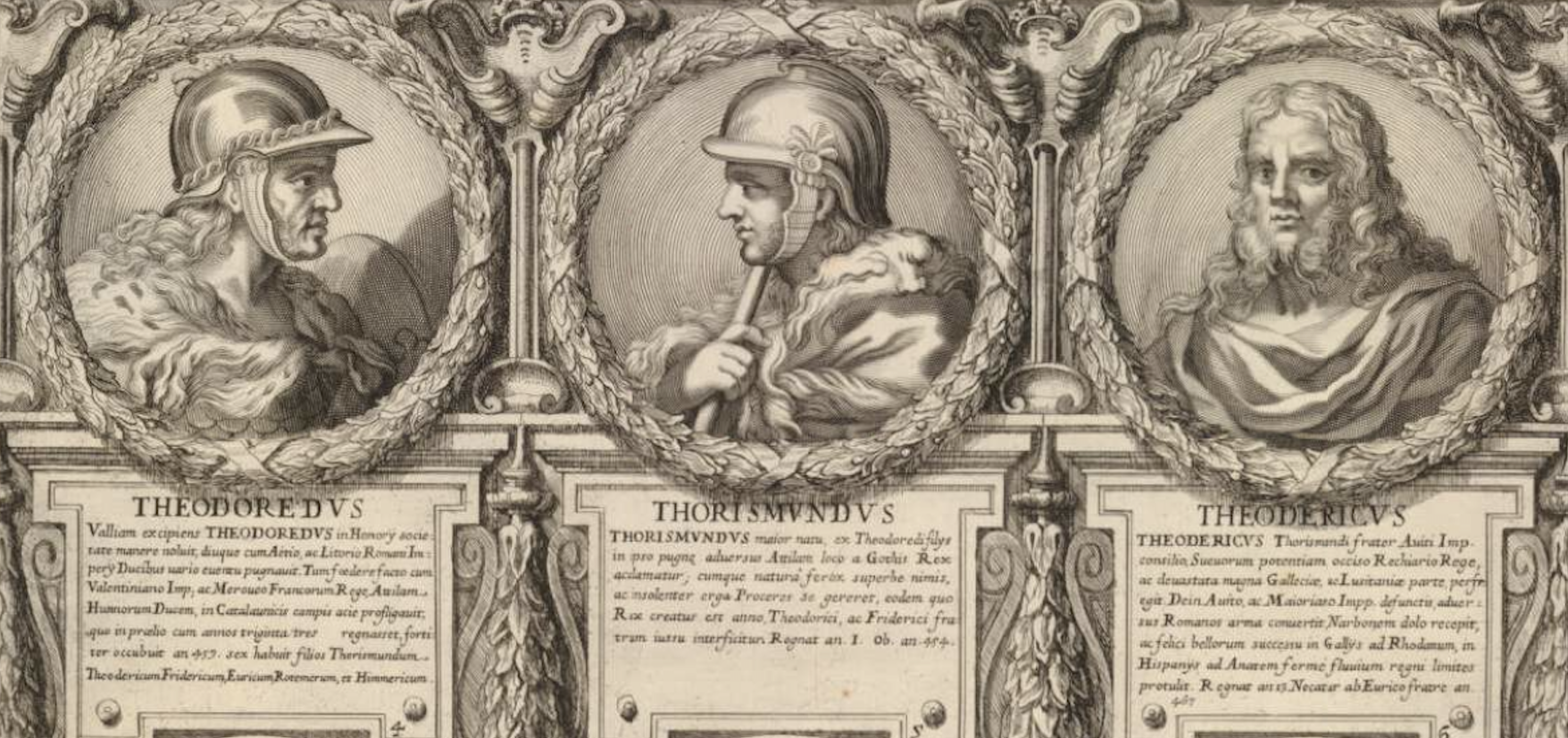

Throughout it all, the Visigoths were led by one man, the longest-lived king in their history to this point, Theodoric I. He’d overseen the settlement in Gaul, and by 450 was around sixty years old—a “barbarian” leader who’d become one of Europe’s elder statesmen. Again, the nature of his quarrel with Attila isn’t clear, but apparently it was credible enough to serve as a pretext for Attila to cross west across the Rhine frontier.

Attila may have made a show of waging war against Theodoric because it would play well in Ravenna (the Italian city then serving as the capital for Emperor Valentinian III and his court). Moreover, Attila was apparently being courted by Gaiseric, King of the Vandals. While Gaiseric had by now crossed over from Spain into North Africa, he still nursed grievances against Theodoric (which we’ll get to once we finish up with the Huns and give the Vandals their own well-deserved narrative arc). A third possible motivation, though one I find unlikely, is that Attila actually sought to make good on the honorary title of Magister militum (master of soldiers) that Aetius had conferred upon him when their relationship had been rosy. According to this latter theory, Attila believed he might make himself Europe’s military master in a formal legal sense.

Attila’s campaign in the west wasn’t just an existential threat to the Western Roman Empire, it was also personally vexing to Aetius, who’d been propping up Roman power in Gaul with the help of Hun mercenaries, even at the expense of other parts of the Empire (including Britain, which the Romans had abandoned four decades earlier). In nominal terms, Attila subduing the Visigoths would seem to be in line with Aetius’ interests. But Aetius was clearly excluded from the messages of friendship that Attila was sending to Valentinian III, and the Roman general must have had some inkling that this campaign was a smokescreen for something else. Both Priscus and Jordanes report that Attila felt he could not achieve his objectives in the west, whatever they were, unless Aetius was removed from his path.

And then, even before the great clash of arms, the Emperor’s sister, Honoria, dropped a gift in Attila’s lap. At the very least, l’affaire Honoria, let us call it, offers a great tidbit of historical gossip, even if its actual significance is debated by historians.

Galla Placidia—the extraordinary woman we first met as the Visigoths were still on the road to Aquitaine—had two children by Emperor Constantius III. One was Valentinian III. The other was his older sister, Justa Grata Honoria, known to history as Honoria. She was about seven when her younger brother took the throne in 426.

Placidia knew from her own experience that marriage to a woman of the Theodosian dynasty was a tempting prospect for ambitious men. And so Honoria was forbidden to marry, lest such nuptials become a conduit for power struggles at court or even full-blown coups. But when it was discovered in 449 that she was having an affair with her chamberlain, new arrangements had to be made quickly. So the free-spirited Honoria was married to one Bassus Herculanus—a wealthy and well-respected senator who was believed to be entirely bereft of ambition. Here was a perfect match for Honoria, insofar as no one asked Honoria about it, which, of course, nobody did.

To save herself from a life of pampered boredom, Honoria wrote a letter to Attila, begging him to come to her rescue. Whether she actually promised herself in marriage (as her inclusion of a ring might suggest), or whether the Hun leader just seized on that idea as a matter of convenience, is an open question.

When all this came to light, her brother, the Emperor (who was by now about 30 years old), threw a proper fit. He tortured and executed the man who’d delivered the message, and would have executed Honoria too, according to Priscus, if Placidia hadn’t interceded. Instead, she was confined for some unknown period of time, while her plight made its way back to Attila, who milked it for all it was worth. Attila could now argue that, in addition to fighting the Visigoths, he’d be fighting for the honour of his beloved (or something like that). Attila sent a message to Ravenna saying that he accepted Honoria’s proposal; that his fiancée should be released immediately; and that, by way of dowry, he’d accept, oh, say, half of the Western Roman Empire.

There’d never be a wedding. We don’t actually know what happened to Honoria after this incident, except that she was placed in her mother’s custody and then disappeared from the historical record. Priscus’ choice of words indicates that Placidia’s intervention saved Honoria from danger at the time. But we don’t know what that danger was or whether Honoria succumbed to it.

By this point in our series, readers will know that while the Western and Eastern components of the Roman Empire were supposed to be two halves of a unified entity, in reality, they each pursued their own interests, and sometimes even fought one another through proxies. In the case of l’affaire Honoria, the Emperor in the east, Theodosius II, blithely advised his western counterpart to just go ahead and send Honoria to Attila—which highlights just how firm a grip Attila had on Constantinople at the time. But Theodosius didn’t get to see how this soap opera ended, as he fell from his horse and died shortly thereafter.

The succession crisis triggered by Theodosius’ death would have been welcomed by Attila, as squabbling in Constantinople would give the Huns a freer hand in the west. But as it happened, the succession fell to a former soldier and court official named Marcianus—usually rendered as Marcian in English—who took a harder line against the Huns than his predecessor. (We don’t know much about Marcian’s backstory in other respects, other than that he sealed the Imperial deal with a marriage to Theodosius’ ferocious sister, Aelia Pulchera, with the unusual proviso that he had to respect her vow of virginity.) Marcian stopped the danegeld-style “tribute” gold payments that the Romans had been sending to Attila, and executed the eunuch Chrysaphius, who’d championed a policy of appeasement toward the Huns while serving as Theodosius II’s chief minister.

Already set to head west, but now facing a potential threat to his eastern flank, Attila had a decision to make. So he sent ambassadors to both Imperial courts. His western envoys came back with the blunt message that Honoria was already engaged to another man and that, even if she did marry Attila, the Roman throne did not pass through the female line. Attila’s eastern ambassadors also were rebuffed: The Huns should expect no further regular gold payments to flow north. There may be the occasional “gift” here and there, but Marcian was determined to reassert Constantinople’s independence from Hunnic extortion.

Yet another complication arose in the autumn of 450 when the Ripuarian Franks—don’t worry, we’ll get to the Franks once we’re done with the Vandals, and I’ll explain what differentiates the Ripurian variety from their Salian rivals—became embroiled in a power struggled waged between two sons of a recently deceased king. One had the support of the Empire, while the other sought support from Attila. Aetius went so far as to adopt the first son, a sign that tensions between the Roman commander and Attila were coming to a head.

Historical sources from the period tell us that Attila found it difficult to make up his mind which path to take. War in the west seemed unavoidable, though it did not necessarily have to happen immediately. Meanwhile, the new situation in Constantinople would need correcting, probably soon, or Marcian might believe that he now held the dominant position in the east.

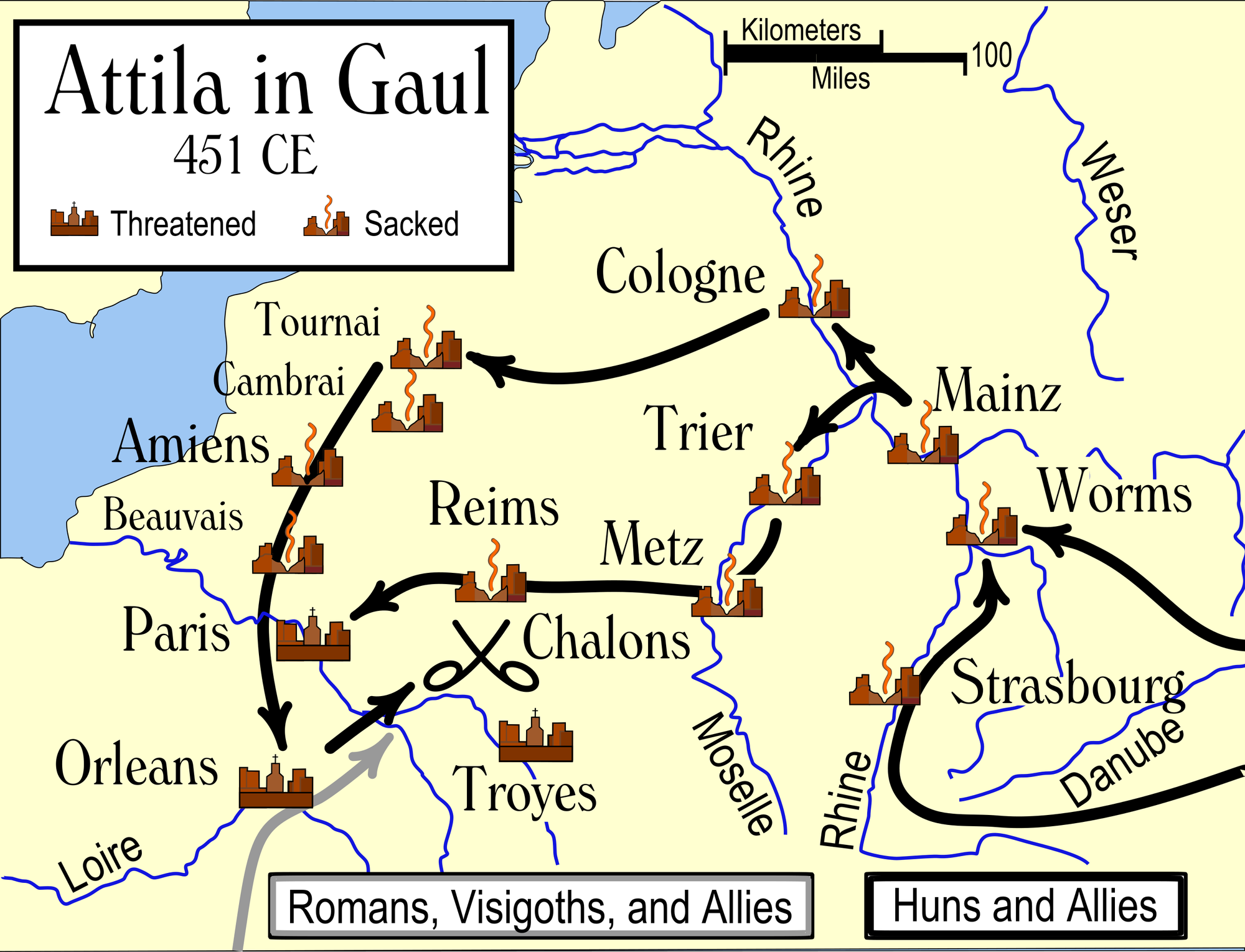

Eventually, Attila settled on his original plan, to strike west, apparently on the principle that it’s advisable to do the more difficult thing first. He probably set out from his base in Pannonia, south of the Danube River, shortly after New Year’s 451. Even now, he was still declaring himself a friend and protector of the Western Emperor’s interests in his quarrels with the Visigoths, though I doubt anyone was buying it by then.

The force that Attila brought with him was, by the slightly hysterical accounts of contemporaries, enormous. Chroniclers confidently offered numbers all the way up to half a million—a completely ridiculous figure, if only because the concentration of so many armed men in any one part of fifth-century Europe would vastly outstrip the available local food supplies, causing all of them to starve. Modern scholars such as E.A. Thompson and Herwig Wolfram place Aetius and his allies’ strength at between 60,000 and 80,000, with most sources agreeing that the two sides would be fairly equal in number when they met on the battlefield. Even at the low end of that estimate, the coming confrontation would be massive.

While on the move, the Hun leader sent another ambassador to Valentinian, insisting again that Honoria be handed over to him; that Valentinian had stolen half of the Empire from his sister; and that he must now correct this misdeed by handing over the purloined territories to Attila, her devoted husband. Obviously, these demands were rejected, though the Imperial court still clung to the hope that Attila would restrict his hostilities to the Visigoths.

That hope imploded with the arrival of Attila’s last messenger. In light of the Romans’ continued stubbornness, the ambassador declared, “Attila, my master and your master, orders that you should make your palace ready for him.” With the cards now all out on the table, Aetius scrambled to mount a response.

Thompson, the twentieth-century Irish-born British historian whose reconstructed timeline of these events informed my research, suggests that Attila’s last messengers to Ravenna may well have arrived when the Hunnic army was already massed along the Rhine, and perhaps even beginning to cross it. Under these urgent circumstances, there’d be no way for Aetius to raise a new army and get it to Gaul, even if he stripped every soldier from Italy (which, unhelpfully, was then being ravaged by famine).

Aetius’ only option was to somehow convince Theodoric—the Visigothic leader whom Attila had claimed to be targeting—to forget the 20 years that the Roman commander had spent trying to thwart Gothic expansion in Gaul. Theodoric had been awaiting the Huns’ arrival with grim determination, and had believed he would have to face the threat alone. Fighting alongside a Roman force would obviously give the Goths better odds.

But Aetius wasn’t just asking Theodoric to fight. He was also asking him to move his Visigothic army east, far out of his home region, so as to assist the Romans in defending Gaul by confronting Attila before he made it all the way to Aquitaine. That request must have seemed like a long shot. And yet, thanks to the persuasive powers of an emissary named Avitus, who’d negotiated with Theodoric successfully in the past, the Gothic king proved agreeable.

Even so, it was very nearly too late. Attila had already crossed the Rhine, and his host was spreading out across northern Gaul by the time Aetius’ available forces linked up with Theodoric. The Roman commander, Jordanes informs us, was leading “a meagre force of auxiliaries without legionaries.” But more allies were gathered as they went, including Burgundians from Savoy, along with Alans, Salian Franks (who’d been settled on Roman territory for some time now), and Saxons, who by now were beginning to appear in small settlements north of the Loire. These all joined Theodoric’s Visigoths and moved to meet the invaders. To put these developments in literary (or cinematic) terms: Gondor called and Rohan answered.

The invader’s army was no less diverse. In addition to the Ostrogoths and various smaller tribes that had been made subjects of Attila and his forebears, other German groups had been swept up as the invasion force moved westward, including Thuringians and Burgundians who still lived east of the Rhine, along with Ripuarian Franks. And so the coming battle would, in ethnic terms, pit “brother against brother” rather than offer a clean division between Romans and Goths on one side and Huns on the other.

Many northern cities in the region fell to the Huns, though it’s difficult to provide an accurate list—in part because the invasion left a significant psychological mark on the population, which, in turn, found expression in myths and folk legends that cloud our understanding of history. Saintly miracles figure in a lot of these legends, as the pagan Huns served as a convenient foil for martyrs and other Christian heroes. The most obvious example is Sainte Geneviève of Paris, whose marathon of massed prayer supposedly turned the Huns away. Orléans, Troyes, and Cologne all have their stories as well. Some of these places may have been taken by the Huns, while others may have simply adopted stories featuring Hunnic antagonists as a means of integrating their civic identity into the region’s shared Christian experience.

We do know that Metz fell on 7 April 451, and that Attila then turned his forces westward, making for Orléans, whose garrison was made up of recently arrived Alans who’d made arrangements with the local Roman nobility. This was one of the strongest Roman towns in the region, and, if taken, would mark a significant prize for Attila. Jordanes suggests that the Alan leader had offered to betray the city to the Huns, but subsequent events cast doubt on that story: The Huns laid siege, but the city’s gates remained shut while the Alans put up a hearty defense. Heavy rains made the siege miserable on both sides as the combined Roman- and Visigoth-led armies raced to confront the besiegers.

Alerted to the approaching force, Attila decided to call off his assault on Orléans and withdraw eastward. Aetius and Theodoric caught up with him somewhere north of Troyes—by tradition, near the town of Châlons-en-Champagne (formerly known as Châlons-sur-Marne), though the exact location is unknown. The two armies faced each other across an expanse of ground dominated by a feature that Jordanes described as the Catalaunian Plain.

Having had ample warning that battle would soon be joined, both sides took their time setting their ranks. Jordanes reports that they were arrayed on either side of a steep hill. That makes very little tactical sense, and even less geographic sense, as Champagne is quite flat. The usual interpretation is that the two armies were on either side of a long ridge, with Aetius commanding the Roman left, and Theodoric and his men on the right. On the other side, Attila was surrounded by leaders of the tribes he and his predecessors had subjugated, most significantly Ostrogoths on the Hunnic left, squared off against their Visigothic cousins, now with generations of separation between them.

The initial action featured a struggle for position and control of the crest of the ridge. Aetius and his men pushed the Huns back on their side of the line, and for a moment it looked like it would be a quick engagement, but Attila shouted encouragement (and possibly threats), and rallied his army into a general charge. The battle then began in earnest. I’m going to let Jordanes take it from here:

Hand to hand they clashed in battle, and the fight grew fierce, confused, monstrous, unrelenting—a fight [of] whose like no ancient time has ever recorded. There such deeds were done that a brave man who missed this spectacle could not hope to see anything so wonderful, all his life long…. A brook flowing between low banks through the plain was greatly increased by blood from the wounds of the slain. Those whose wounds drove them to slake their thirst drank water mingled with gore.

The Visigoths flew across the plain, fighting bravely, and fell upon the Huns, nearly reaching Attila himself, who withdrew with his force of bodyguards to a fortified camp. Darkness brought an end to the battle before any real conclusion, however, and there was apparently a great deal of riding around in the dark. At one point, Thorismund, Theodoric’s oldest son (and soon to be his successor), stumbled on the Huns’ baggage train, thinking it was his own, and was dragged from his horse and nearly killed before being rescued by some of his men. Aetius likewise became separated from the main body of the armies and had a hair-raising few hours before he found his way back to his own camp.

In the morning, the dead were piled high on the field. The Huns remained in their camp, and there was some debate about what they should do next. During this lull, the body of Theodoric was found, “where the dead lay thickest, as happens with brave men.” Jordanes records two different accounts of his death. One has it that he’d been thrown by his horse and trampled. The other was that he’d died by the spear of one Andag of the Ostrogoths (who also happened to be the father of Jordanes’ patron, Gunthigis, so make of that what you will).

The Visigoths buried him there on the plain, and mourned their king. Jordanes again:

Tears were shed, but such as they were accustomed to devote to brave men. It was death indeed, but the Huns are witness that it was a glorious one. It was a death whereby one might suppose the pride of the enemy would be lowered when they beheld the body of so great a king borne forth with fitting honours.

Jordanes reported that 165,000 were killed at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, which is patently absurd, being significantly more than the total number of fighting men who likely took part. What’s indisputable, though, is the importance of the battle in the legends and self-image of the Goths. While sources close to the event framed it as Aetius’ victory, as time went on, it came to be seen more and more as a victory for Theodoric, Thorismund, and the Gothic people.

In one legend, the fighting was so fierce that the souls of the slain could be seen, still fighting as they rose up toward the heavens. Theodoric’s legend has even come all the way down to us in modern popular culture, as at least one of the inspirations for J.R.R. Tolkein’s Théoden of Rohan, who dies fighting the forces of evil at the “Battle of the Pelennor Fields.”

The Battle of the Catalaunian Fields would prove to be the most significant engagement of Attila’s invasion of Gaul, as it forced him to return east to regroup. But its long-term significance is still up for debate. While the writers of the time painted it in apocalyptic terms, Attila would be back in the west less than a year later. So to the extent he left Champagne a broken man, he healed quickly.

With Theodoric dead, command of his army fell to his son Thorismund. Aetius told the new Visigothic leader that, rather than pursue Attila and avenge his father, he should return to Aquitaine and ensure that none of his relatives seized the Visigothic throne in his absence. He likewise suggested to his adopted son, the aforementioned Frankish prince, that he should see to his lands as well, since, without Attila’s support, his rival brother was now vulnerable. Both men agreed with Aetius, and the allied army dissolved.

Strange as it may seem, the Roman commander wasn’t seeking to bring about the complete destruction of the Huns. Falling back on the age-old Roman instinct to prevail over barbarians by pitting them against one another, Aetius still believed he could enlist Hunnic mercenaries in a bid to keep the Visigoths from encroaching into Roman-controlled areas of Gaul. He was, in short, seeking to reconstruct the shaky status quo of the 440s, a project that (spoiler alert) was destined to fail.

As for Attila, he was in a foul mood when he returned to his base in Pannonia. Marcian had sent a new ambassador from Constantinople, but Attila wouldn’t even grant him an audience. He was furious to hear that this new man had come with no tribute payment, and Attila ordered him to hand over whatever diplomatic gifts he had brought with him and be gone. The ambassador, a man named Apollonius who deserves to be remembered for his courage, said that he would present his gifts when he was received as an ambassador should be. The Hun could kill him if he wanted, but then they would not be gifts, only the rewards of banditry. On Attila’s orders, he returned to Constantinople, having achieved nothing except keeping his organs in all the right places.

Attila then launched a few incursions into Illyricum (the western Balkans), presumably as a means to remind Marcian that the Huns weren’t going anywhere. The campaign was serious enough to prompt a change of venue for a great church council from Nicaea to Chalcedon. But Attila’s mind was elsewhere. He’d been stung by the outcome of his Gallic adventure. More importantly, from his standpoint, his legend had been tarnished. For that reason alone, I’m guessing, he felt he had no choice but to seek a rematch.

This time, Attila wouldn’t bother attacking the Goths. Nor was he distracted by Marcian’s continued insolence. Attila was now focused on the one man whom he saw as the architect of his defeat at the Catalaunian Plains. And so he readied his forces for a new campaign that would be directed not at Gaul, but at the heart of Aetius’ power in Italy itself.