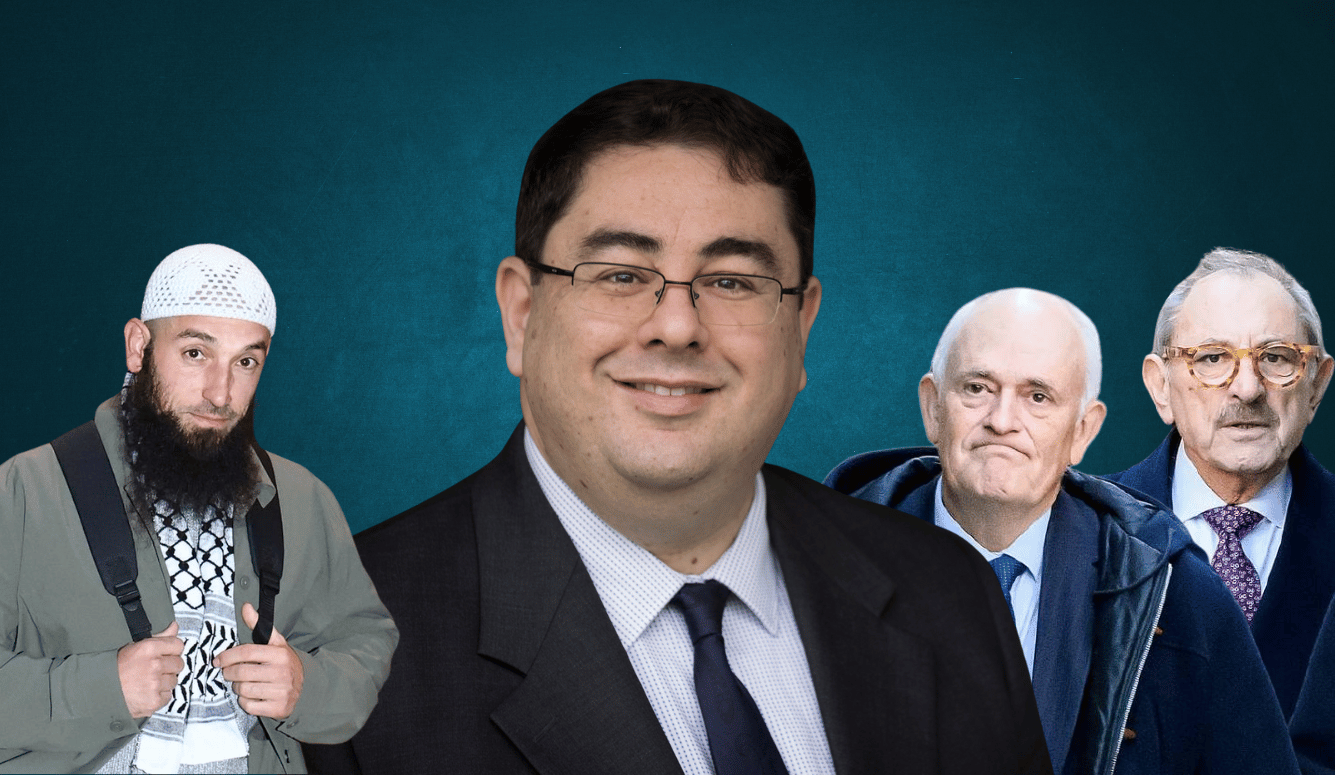

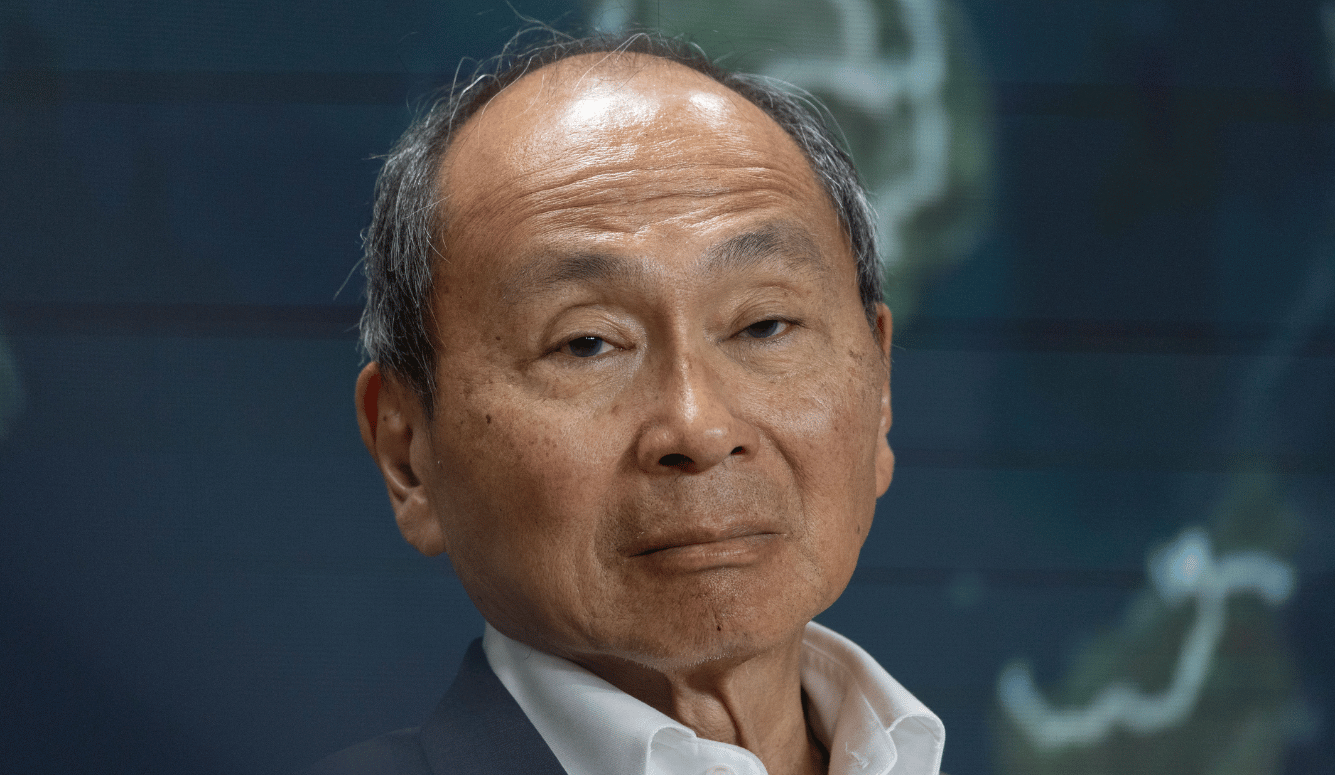

On 9 July, Francis Fukuyama sat down with Quillette’s Matt Johnson for a wide-ranging discussion about the return of political patrimonialism, the liberal “abundance” agenda, social capital and trust, wokeness, populist anger, protectionism, the struggle for recognition and the struggle for democracy everywhere.

Quillette: A major theme of your Political Order series is the importance of moving beyond patrimonialism [when political power is distributed according to patronage and loyalty] in the establishment of modern states. Under the Trump administration, a process of repatrimonialisation now appears to be underway on a vast scale. Why is this happening and what do you think the consequences will be?

Francis Fukuyama: This is a case where the democratic part of liberal democracy has triumphed over the liberal part. The liberal part really has to do with the rule of law and constraints on the executive that are reflected in constitutional checks and balances. And I think that populist movements rely on democratic legitimacy to then build power, and they don’t like the constraints that limit the power of the president. So, you hear that in people like Stephen Miller saying, “What are these courts? They have no business telling us we can’t do what we want to do.” And I think that’s been the pattern in Hungary, India, Slovakia, and a lot of other places. You have elections that produce populist leaders who then use their political capital to try to erode the checks and balances that constrain them. And that’s what we’re seeing in the United States right now.

Q: Why is patrimonialism so detrimental to good governance?

FF: The essence of patrimonialism is that the ruler thinks that the government is, in a sense, his own possession, and he can do whatever wants with it, including enrich himself. Over the centuries, you’ve had patrimonial states where the ruler’s main interest is in self-enrichment and just increasing their own personal power. So, this is nothing new. We only broke out of this in the West a couple of hundred years ago. In China, you have a longer history of non-patrimonial government. But it’s actually quite delicate to get a government that seems to be dedicated to a public interest as opposed to the private interest of the ruler.

One of the themes of my Political Order books is that there’s something in a sense unnatural about meritocracy—that we naturally want to reward our friends and family—and it’s only under certain institutional conditions that we’ve been able to create the idea that you should be serving the public interest as opposed to your own interest. And it doesn’t occur to everybody, and it obviously doesn’t occur to Donald Trump. Apart from the erosion of checks and balances that he has been attempting, he’s also running the most corrupt administration in American history as far as I can tell. Just openly using the White House as a means of enriching his family and his family’s businesses.

Q: Do you think the tariffs are a genuine political commitment by Trump? He’s been a protectionist for many years, but tariffs are also a perfect vehicle for patrimony and patronage.

FF: I think it’s both. He was hoping that once he declared these retaliatory tariffs that everybody would come to him begging for exemptions. That’s what happened in his first term. And it turns out that people are on to this game, so it hasn’t quite worked out for him as well as he thought it would. Definitely, a side benefit of having this discretionary power over tariffs is that he can also benefit personally as people come to him. It’s just like pleading with the king—you want an audience with the king so you can get an exemption to some general rule.

Q: How does this era of patrimonialism differ from previous eras?

FF: It’s not clear that it does. In my Political Order books, I argue that with each civilisation—with China, for example, or with the Ottoman Empire in Europe—you had these efforts to get beyond a patrimonial state and establish a modern, impersonal one. But all of them eventually fell back into patrimonialism. I think it’s just this constant pull. You need impersonal government, but it’s hard to maintain because of the temptations of power once you create a government that actually concentrates sufficient power to run a modern state. So, I’m not sure we’re going to get out of this anytime soon.

Q: Do you think Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance agenda is a good first step toward restoring faith in democratic institutions? Could you talk about how their thesis relates to your longstanding concerns over political decay, particularly what you describe as “vetocracy” in the United States?