Activism

Sexual Perversity in Ontario

An absurd trial, a prurient media circus, and a failure of feminist ethics.

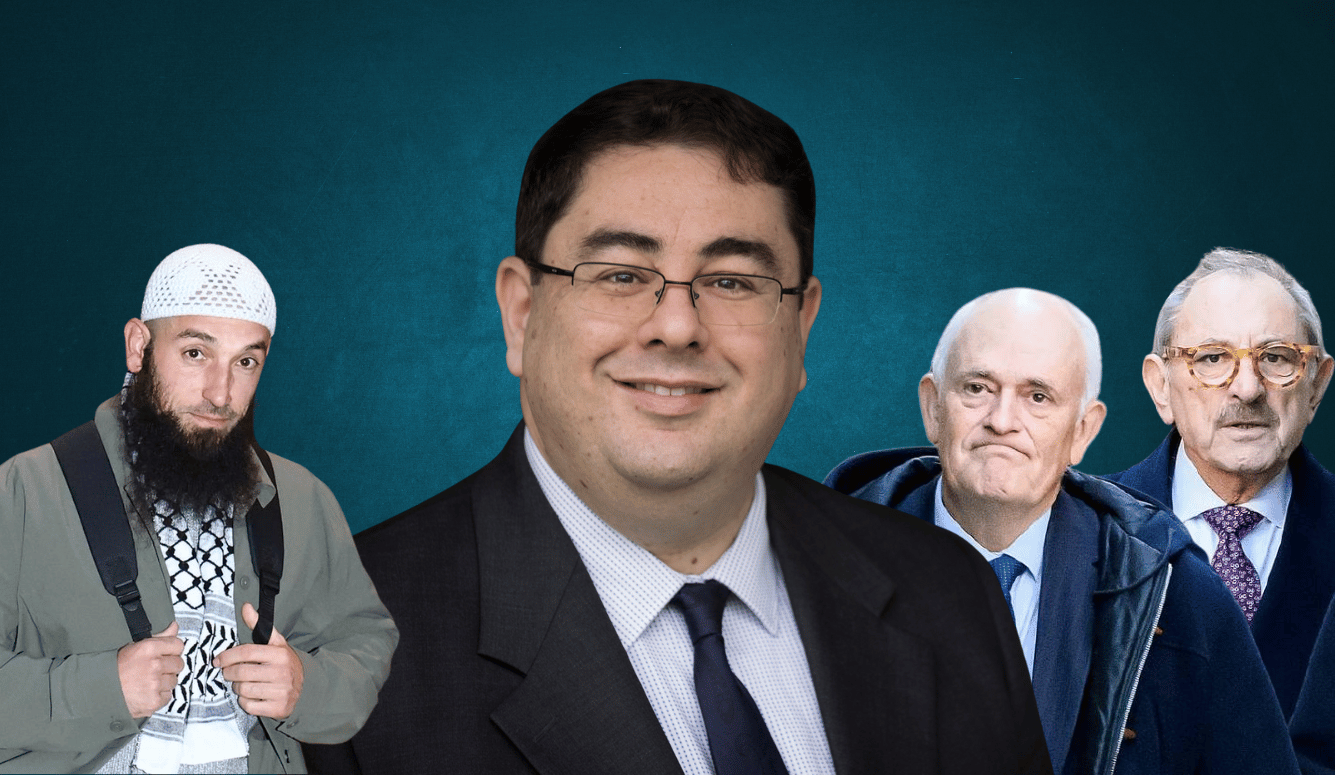

On Thursday 24 July, five former World Junior Hockey players were acquitted by Ontario Superior Court Judge Maria Carroccia following an eight-week sexual-assault trial that should never have seen the inside of a courtroom. In Canada, the trial rapidly became a prurient media circus, so all Canadians—including those, like me, who felt only fremdschämen for all concerned—have been privy to the lurid details of a consensual group-sex session in a hotel room back in 2018. And how do we know that the sex was consensual? Because the young female complainant, known only as E.M., recorded a video on the night she had sex with all five defendants, in which she laughed: “It was all consensual. Are you recording me? ’K, good. You are so paranoid. Holy. I enjoyed it. It was fine. I’m so sober—that’s why I can’t do this right now.”

On the night of the incident, the defendants were in London, Ontario, for a Hockey Canada gala. E.M., who was twenty years old at the time, met them at a local bar and then accompanied one of them back to his hotel room for what she still agrees was consensual oral and penetrative sex. The defence alleged—and the prosecution denied—that it was E.M. who suggested that other players be invited to the hotel room because she wanted “a wild night.” She did acknowledge that she was naked when they arrived and that she did not put her clothes on. The defence argued that E.M. then invited all of the young men present to have sex with her and that she consented to every sex act that followed. The prosecution countered that she was drunk, intimidated, and coerced and that the video she recorded exonerating the defendants was actually proof they had done something wrong, which is why they told her to record it.

The feelings and state of mind of the complainant were central to the trial, and her consent video was hotly debated in court and in the press. Did it prove consent or did it suggest the opposite? Did she really want to consent or not? Did she consent at the time but regret it afterwards? Did she not consent but say that she did? Did the young men somehow know or intuit that she didn’t consent, or that she was conflicted? If consent can, as the prosecution contended, be “withdrawn at any time,” does that “anytime” include seven years after the fact? And if so, what would the implications of that kind of legal precedent look like? The case was a lot less like a traditional he said/she said affair than a she said/she said instance of confusion, excitement, danger, and regret.

There was also some procedural drama along the way. A mistrial was declared by Justice Carroccia just three days after the jury was selected following an inappropriate interaction between one of the jurors and a member of the defence team. A new fourteen-member jury was duly empanelled, but they too were subsequently discharged after a juror complained that a member of the defence team had mocked her. Rather than restart the trial a second time, both the defence and the prosecution agreed that the case would be heard and decided by Justice Carroccia alone.

If the Crown assumed that a female judge was likely to rule in their favour, they were to be disappointed. In her judgement, Carroccia concluded that, “on the totality of the evidence,” it was E.M., not the defendants, who had been the sexual instigator and “aggressor.” She had masturbated in front of them, demanded “Is anyone going to bang me?,” and even called the young men “pussies” for their reluctance to have sex with her. Given the evidence heard in court, the judge decided it would be prudent to treat the complainant’s account with scepticism:

It also causes the court concern that the complainant acknowledged that where she has gaps in her memory, she filled those gaps with assumptions. This causes concern in relation to the witness’s credibility and her reliability. The complainant also gave a vague answer when it was suggested to her in cross-examination that it was easier for her to deny the deliberate choices she made on June 18 and 19, 2018, than to acknowledge the shame, guilt, and embarrassment about those choices. She did not deny the suggestion, she said: “I don’t know. I’m kind of struggling to understand that” and went on to explain that she blames herself and that other people should be held accountable, but it was “a combination of things.”

There is no reason to default to a standard of believing a woman when copious evidence disconfirms or casts doubt on that woman’s account, including surveillance footage, text correspondence, competing witness testimony, and the internal inconsistencies of her own statements. “On several occasions,” Carroccia added, “the complainant referred to her evidence as ‘her truth’ rather than ‘the truth,’ which seemingly blurs the line between what she believes to be true and what is objectively true.”

That this particular case was decided by a female judge ought to have made it harder to argue that the outcome indicates institutional bias or misogyny. Nevertheless, indefatigable activists gathered outside the courthouse to express their displeasure with the verdicts and their unshakeable solidarity with E.M. “Over the last few weeks and five cross-examinations in court, E.M. has faced almost every harmful and victim-blaming sexual assault myth in existence,” complained the Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres in a statement.